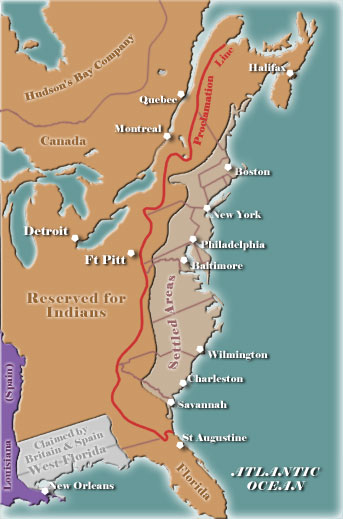

In the fall of 1763, a royal decree was issued that prohibited the North American colonists from establishing or maintaining settlements west of an imaginary line running down the crest of the Appalachian Mountains. It stated:

We do therefore, with the Advice of our Privy Council, declare it to be our Royal Will and Pleasure, that no Governor or Commander in Chief in any of our Colonies of Quebec, East Florida, or West Florida, do presume, upon any Pretence whatever, to grant Warrants of Survey, or pass any Patents for Lands beyond the Bounds of their respective Governments, as described in their Commissions: as also that no Governor or Commander in Chief in any of our other Colonies or Plantations in America do presume for the present, and until our further Pleasure be known, to grant Warrants of Survey, or pass Patents for any Lands beyond the Heads or Sources of any of the Rivers which fall into the Atlantic Ocean from the West and North West, or upon any Lands whatever, which, not having been ceded to or purchased by Us as aforesaid, are reserved to the said Indians, or any of them.The Proclamation 0f 1763, as it is known, acknowledged that Indians owned the lands on which they were then residing and white settlers in the area were to be removed. However, provision was made to allow specially licensed individuals and entities to operate fur trading ventures in the proscribed area. There were two motivations for this policy:

The reaction of colonial land speculators and frontiersmen was immediate and understandably negative. From their perspective, risking their lives in the recent war had been rewarded by the creation of a vast restricted native reserve in the lands they coveted. Most concluded that the proclamation was only a temporary measure and a number ignored it entirely and moved into the prohibited area.

Almost from its inception, the proclamation was modified to suit the needs of influential people with interests in the American West. This included many high British officials as well as colonial leaders.

Beginning in 1764, portions of the Proclamation Line were adjusted westward to accommodate speculative interests. Later, in 1768, the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix formally recognized the surrender of transmontane lands claimed by the Iroquois.

The Proclamation of 1763 was a well-intentioned measure. Pontiac’s Rebellion had inflicted a terrible toll on the frontier settlements in North America and the British government acted prudently by attempting to avoid such conflict in the foreseeable future.

The colonists, however, were not appreciative and regarded the new policy as an infringement of their basic rights. The fact that western expansion was halted at roughly the same time that other restrictive measures were being implemented, made the colonists increasingly suspicious.

The reaction of colonial land speculators and frontiersmen was immediate and understandably negative. From their perspective, risking their lives in the recent war had been rewarded by the creation of a vast restricted native reserve in the lands they coveted. Most concluded that the proclamation was only a temporary measure and a number ignored it entirely and moved into the prohibited area.

Almost from its inception, the proclamation was modified to suit the needs of influential people with interests in the American West. This included many high British officials as well as colonial leaders.

Beginning in 1764, portions of the Proclamation Line were adjusted westward to accommodate speculative interests. Later, in 1768, the first Treaty of Fort Stanwix formally recognized the surrender of transmontane lands claimed by the Iroquois.

The Proclamation of 1763 was a well-intentioned measure. Pontiac’s Rebellion had inflicted a terrible toll on the frontier settlements in North America and the British government acted prudently by attempting to avoid such conflict in the foreseeable future.

The colonists, however, were not appreciative and regarded the new policy as an infringement of their basic rights. The fact that western expansion was halted at roughly the same time that other restrictive measures were being implemented, made the colonists increasingly suspicious.