By the spring of 1768, tensions between radical Bostonians and British officials in the city were reaching dangerous proportions. Much of the unrest was rooted in the enforcement of the unpopular Townshend Acts, while the increasing tendency of the British Navy to impress American citizens caused further turmoil.

In April, two customs officials boarded the Lydia, a ship belonging to John Hancock, New England’s wealthiest citizen and a leading critic of British policies. Citing a lack of proper authorization, the inspectors were forcibly removed and taken ashore. Criminal charges were quickly filed against Hancock, but later dropped when it was ascertained that the officials had not secured Writs of Assistance to sanction their search. Hancock escaped legal action in this event, but became a marked man for the miffed customs service.

Hancock did not have to wait long. On June 10, customs officials seized another of his vessels, the sloop Liberty, on trumped up charges related to its cargo of Madeira wine. An order was given to the waiting warship Romney to tow the Liberty away from Hancock’s dock to relative isolation in the harbor. The Sons of Liberty incited a mob that gathered on the wharf and vented its anger on the customs house. Windows were broken and a small pleasure craft belonging to one of the collectors was seized. The boat was dragged through the city and became the featured attraction at a huge bonfire on Boston Common.

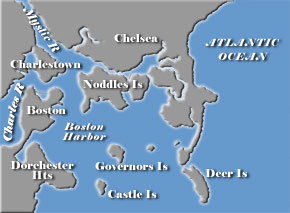

The customs officials were unharmed during the unrest, but prudently fled to Castle William in Boston harbor.

On June 13, the Sons of Liberty held a meeting at Faneuil Hall with James Otis presiding. A committee was appointed to petition Governor Francis Bernard for the removal of the Romney and an end to heavy-handed actions by British officials. The governor courteously received a delegation the following day and promised to do all within his power to effect conciliation; he also made a specific promise to end impressment.

Bernard was clearly in a bind. No soldiers had been stationed in the city at that point and he was secretly trying to arrange such a deployment. Under orders from London, the governor appeared before the Massachusetts assembly and requested the revocation of a circular letter sent to the other colonies in February urging united action against the Townshend Acts. Sam Adams and Otis, the chief authors of the letter, gave lengthy responses to Bernard’s speech. When a vote was finally taken, 92 members voted against rescinding and only 17 for. Great celebrations followed that night in the city, where some patriots claimed to have drunk 92 toasts to their victory.

Not content with denying the governor’s appeal, the assembly voted approval of a list of charges against Bernard and sent them off to the king. The 17 “rescinders” became the object of public scorn, but none was physically harmed.

In July, Governor Bernard dissolved the Massachusetts assembly. That summer became one of virtual mob rule in Boston.

Hancock did not have to wait long. On June 10, customs officials seized another of his vessels, the sloop Liberty, on trumped up charges related to its cargo of Madeira wine. An order was given to the waiting warship Romney to tow the Liberty away from Hancock’s dock to relative isolation in the harbor. The Sons of Liberty incited a mob that gathered on the wharf and vented its anger on the customs house. Windows were broken and a small pleasure craft belonging to one of the collectors was seized. The boat was dragged through the city and became the featured attraction at a huge bonfire on Boston Common.

The customs officials were unharmed during the unrest, but prudently fled to Castle William in Boston harbor.

On June 13, the Sons of Liberty held a meeting at Faneuil Hall with James Otis presiding. A committee was appointed to petition Governor Francis Bernard for the removal of the Romney and an end to heavy-handed actions by British officials. The governor courteously received a delegation the following day and promised to do all within his power to effect conciliation; he also made a specific promise to end impressment.

Bernard was clearly in a bind. No soldiers had been stationed in the city at that point and he was secretly trying to arrange such a deployment. Under orders from London, the governor appeared before the Massachusetts assembly and requested the revocation of a circular letter sent to the other colonies in February urging united action against the Townshend Acts. Sam Adams and Otis, the chief authors of the letter, gave lengthy responses to Bernard’s speech. When a vote was finally taken, 92 members voted against rescinding and only 17 for. Great celebrations followed that night in the city, where some patriots claimed to have drunk 92 toasts to their victory.

Not content with denying the governor’s appeal, the assembly voted approval of a list of charges against Bernard and sent them off to the king. The 17 “rescinders” became the object of public scorn, but none was physically harmed.

In July, Governor Bernard dissolved the Massachusetts assembly. That summer became one of virtual mob rule in Boston.