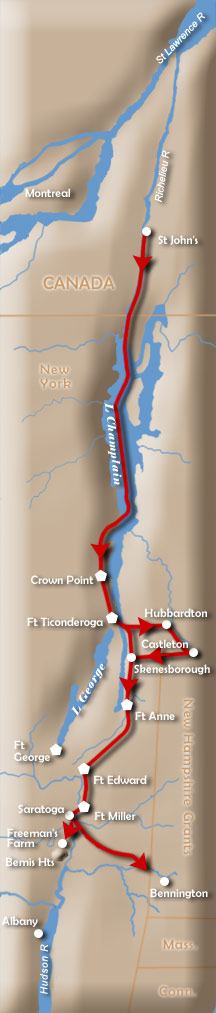

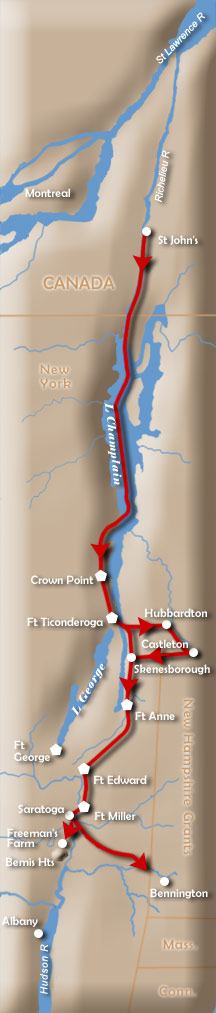

Burgoyne Campaign of 1777

In early 1777, American military leaders and members of Congress were aware that Major General John Burgoyne maintained a considerable force in Canada, but assumed that when those forces were readied for action it would be in an offensive against Philadelphia, the American capital city. Few colonists believed that the British would again try an assault southward down Lake Champlain, as they had done unsuccessfully in the early stages of the war.

Despite the American assumption, Burgoyne had received the consent of Lord Germain and George III for the southward move. On June 17, British forces departed from St. John’s in a huge procession of more than 8,000 men, extensive artillery and dozens of baggage wagons. By the end of the month, the army had reached the first important rebel strongholds and commenced a series of encounters:

- Fall of Ticonderoga (July 6, 1777). Burgoyne’s army arrived at the poorly defended Fort Ticonderoga on June 30 and prepared for a siege. The British managed to take the “American Gibraltar” without resistance following the evacuation of the post by Arthur St. Clair's forces.

- Fall of Skenesborough. (July 6, 1777). Patriot defenders made little effort to hold the "birthplace of the American Navy."

- Fall of Fort Anne (July 7, 1777). The American plan to hold this outpost was abandoned after it was learned that Indians had joined their British allies. The fort was set on fire and the defenders fled south to Fort Edward.

- Battle of Hubbardton (July 7, 1777). To the astonishment of many British military leaders, the Americans fought a successful rear guard action that stopped the pursuit of St. Clair’s retreating forces.

Burgoyne's army was slowed by delaying tactics used by Philip Schuyler's forces — harassing the opponent's army, destroying crops and bridges, and felling huge trees across the invaders' path.

Fall of Fort Edward (July 31, 1777). The approach of Burgoyne's long-delayed army prompted Schuyler to abandon the fort on July 29. The Americans retreated down the Hudson River to Saratoga. The British occupied Fort Edward on July 30.

On August 4, Congress removed Schuyler and named Horatio Gates to head the Northern Command.

- Battle of Bennington (August 16, 1777). American forces under John Stark and Seth Warner soundly defeated a German foraging party and a relief column.

Following Bennington, Burgoyne’s army took up temporary quarters at Fort Miller near Saratoga, present-day Schuylerville, New York, and waited three weeks for supplies.

The American Northern Command grew in numbers during the lull in action. Benedict Arnold arrived back in Albany with his troops flushed with their recent success in the Mohawk Valley. Washington also dispatched forces from the Hudson Highlands as well as Daniel Morgan's veteran riflemen to bolster Gates' army. On September 8, the Americans began a northward advance and later occupied a hilltop position 300 feet above the Hudson River on Bemis Heights.

Burgoyne crossed to the west side of the Hudson on September 13, but was uncertain of his foe's location. A chance encounter on the 18th led him to the decision to strike against the American forces. The British were running low on supplies and an overt action was needed to break through to Albany:

- Battle of Freeman's Farm (September 19, 1777). Sometimes called the First Battle of Saratoga, Burgoyne's army reached its southernmost point, but failed in an attempt to take a vital elevated position. The British avoided disaster by a successful retreat.

Heartened by the news of Clinton's long-delayed advance up the Hudson, Burgoyne dug in and waited for the desperately needed assistance. Clinton, however, failed in his effort and left Burgoyne little alternative but to make a last-ditch attempt to break out of his trap:

- Battle of Bemis Heights (October 7, 1777). Also called the Second Battle of Saratoga, this decisive encounter involved the combined efforts of Daniel Morgan, Benedict Arnold and Ebenezer Learned to successfully halt Burgoyne's advance. The British pulled back during the night and later retreated to the hills outside Saratoga.

A cessation of hostilities was arranged on October 13 and a formal surrender took place under the terms of the Convention of Saratoga on the 17th. The unsuccessful Burgoyne invasion demonstrated the futility of conducting an operation in hostile territory, far from the invaders' sources of supplies and reinforcements.