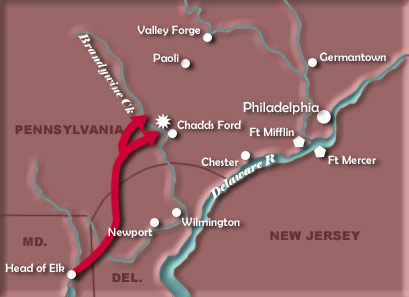

Major General William Howe’s fleet arrived at Head of Elk, Maryland on August 23, 1777, which ended a miserable voyage. Torrential rains greeted the British as they began their march across Delaware into Pennsylvania. Howe anticipated the quick capture of Philadelphia, which, in his opinion, would unleash Loyalist support in the Middle States. He then planned to rejoin the northern campaign on the Hudson River.

George Washington attempted to make the most of a precarious situation. On August 24, he marched the Continental Army in single file through Philadelphia in hopes that this show of force would act to dampen Loyalist passions and buoy those of partisans. The Americans then moved south and placed themselves between the advancing British army and their target, Philadelphia.

The first important encounter of the Philadelphia Campaign occurred on September 11 near Chadd’s Ford on Brandywine Creek. British forces under General William von Knyphausen struck at the American center, but the major effort was directed against the right flank with British forces under the command of Charles Cornwallis. Americans led by John Sullivan were routed and an orderly withdrawal was brought about only by the actions of Nathanael Greene.

British casualties at Brandywine numbered 576, while estimated American losses were more than 400, and Lafayette was wounded. Washington was forced to pull back toward Philadelphia, pausing first at Chester and later moving north to Germantown. Washington had again been outmaneuvered by Howe, but Howe had repeated his failure to deal a knockout blow to the Continental Army. Brandywine was indeed a British victory, but Washington succeeded in his most important task — to keep his army in the field, even if it was in retreat.

Congress was in turmoil. Some delegates pressed for Sullivan's removal, but Washington refused to sanction that move. In fear of the oncoming British, Congress fled to Lancaster on September 19 and later to the more remote town of York.

The first important encounter of the Philadelphia Campaign occurred on September 11 near Chadd’s Ford on Brandywine Creek. British forces under General William von Knyphausen struck at the American center, but the major effort was directed against the right flank with British forces under the command of Charles Cornwallis. Americans led by John Sullivan were routed and an orderly withdrawal was brought about only by the actions of Nathanael Greene.

British casualties at Brandywine numbered 576, while estimated American losses were more than 400, and Lafayette was wounded. Washington was forced to pull back toward Philadelphia, pausing first at Chester and later moving north to Germantown. Washington had again been outmaneuvered by Howe, but Howe had repeated his failure to deal a knockout blow to the Continental Army. Brandywine was indeed a British victory, but Washington succeeded in his most important task — to keep his army in the field, even if it was in retreat.

Congress was in turmoil. Some delegates pressed for Sullivan's removal, but Washington refused to sanction that move. In fear of the oncoming British, Congress fled to Lancaster on September 19 and later to the more remote town of York.