The British three-pronged offensive of 1777 had slated William Howe to lead forces up the Hudson from New York City and rendezvous with John Burgoyne’s army at Albany. Howe, however, chose to pursue a campaign for Philadelphia, leaving Henry Clinton to lead the southern column.

In September, Clinton sent a letter to an increasingly worried Burgoyne, indicating that reinforcements had arrived in New York City and that the southern prong was preparing to render assistance. Clinton, showing little concern for haste, took two more weeks before departing with his force of about 4,000 men.

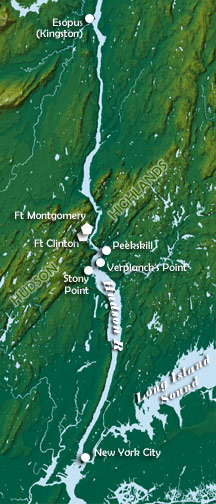

In early October, Clinton sent advance forces against two American installations in the Hudson Highlands — Forts Clinton and Montgomery. The former was named for its commander and the current New York governor, George Clinton, and the latter was commanded by his brother James. The forts held negligible garrisons, but tended a chain across the Hudson River that denied passage to enemy vessels. Verplanck’s Point fell to the British on October 5 and the two forts capitulated on the following day.

On October 9, Clinton, who received Burgoyne’s desperate appeal for aid, dispatched a portion of his fleet. Pressing northward up the Hudson, the flotilla was harassed from both banks by militiamen demonstrating their marksmanship. On the 16th, unaware that Burgoyne was engaged in surrender talks, the advance party burned the town of Esopus (later Kingston), recently the meeting site of the New York assembly.

A few days later, Clinton received word that his advance force had been unable to reach Burgoyne. Then he received orders from Howe to pull back to New York City and send reinforcements to Philadelphia.

Clinton's northward advance was successful only by taking several minor rebel positions along the Hudson and destroying a handful of enemy vessels. The major objective to reinforce Burgoyne and the lesser aim to create a diversion were complete failures. A possible reason for Clinton's lethargy was that he was intensely concerned about his own career advancement and saw himself as the logical replacement for Howe as commander-in-chief. He felt little motivation to advance Burgoyne's prospects or any other potential rival.

In September, Clinton sent a letter to an increasingly worried Burgoyne, indicating that reinforcements had arrived in New York City and that the southern prong was preparing to render assistance. Clinton, showing little concern for haste, took two more weeks before departing with his force of about 4,000 men.

In early October, Clinton sent advance forces against two American installations in the Hudson Highlands — Forts Clinton and Montgomery. The former was named for its commander and the current New York governor, George Clinton, and the latter was commanded by his brother James. The forts held negligible garrisons, but tended a chain across the Hudson River that denied passage to enemy vessels. Verplanck’s Point fell to the British on October 5 and the two forts capitulated on the following day.

On October 9, Clinton, who received Burgoyne’s desperate appeal for aid, dispatched a portion of his fleet. Pressing northward up the Hudson, the flotilla was harassed from both banks by militiamen demonstrating their marksmanship. On the 16th, unaware that Burgoyne was engaged in surrender talks, the advance party burned the town of Esopus (later Kingston), recently the meeting site of the New York assembly.

A few days later, Clinton received word that his advance force had been unable to reach Burgoyne. Then he received orders from Howe to pull back to New York City and send reinforcements to Philadelphia.

Clinton's northward advance was successful only by taking several minor rebel positions along the Hudson and destroying a handful of enemy vessels. The major objective to reinforce Burgoyne and the lesser aim to create a diversion were complete failures. A possible reason for Clinton's lethargy was that he was intensely concerned about his own career advancement and saw himself as the logical replacement for Howe as commander-in-chief. He felt little motivation to advance Burgoyne's prospects or any other potential rival.