Fort Frontenac

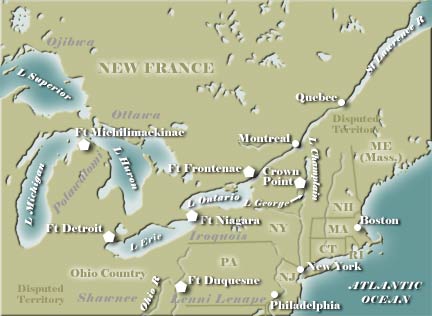

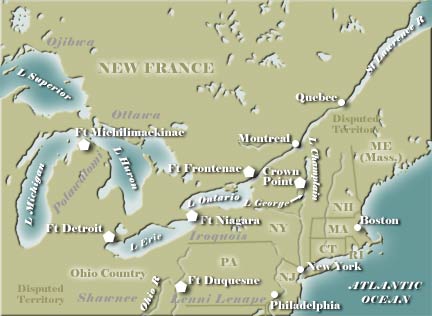

The northeastern corner of Lake Ontario attracted the attention of early European explorers because of the potential for a harbor facility and easy access to the headwaters of the St. Lawrence River. The Comte de Frontenac, governor of New France, dedicated Fort Cataraqui on this site in July 1673 and later renamed the wooden palisaded structure for himself. Frontenac granted the fort and surrounding lands to a colleague, Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle, the famed explorer of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. Frontenac, however, retained full rights to the area’s fur trade and hoped to control that lucrative business throughout the Great Lakes from this strategically located installation.

La Salle spent little time at Fort Frontenac, but did use it as the headquarters for his exploratory ventures. The fort was remodeled and enlarged on several occasions, and by 1685 the wooden walls had given way to more formidable limestone barriers. A small French settlement flourished in the vicinity, as well as an Indian village.

Fort Frontenac made use of its strategic location and was the key position from which supplies and reinforcements were sent to the other French installations on the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.

Nonetheless, the stability and utility of Fort Frontenac were threatened from two directions:

- La Salle’s inattention to financial matters had allowed creditors to gain control of the facility. His interest had been in exploration, theirs was in making profits.

- A graver threat was posed by the neighboring Iroquois, who had allied themselves with the British and looked for every opportunity to oust the French. A siege of the fort in 1688 resulted in the loss of many of the defenders' lives, mostly from disease. The following year, the government of New France ordered the facility's closure, claiming that it was too remote to be defended properly. Explosive charges were placed in the walls and detonated as a means to render the fort useless to the enemy.

King William's War, the first of a series of conflicts between France and England, raged through much of the 1690s. The arrival of peace brought a renewal of interest in fortifying the area. The new Fort Frontenac never became a first-class installation and would remain the shadow of more substantial forts at

Detroit, Michilimackinac and Niagara. By the 1750s, Fort Frontenac was primarily a supply warehouse and harbor facility. As the

French and Indian War approached, an effort was made to bring the fort up to the standards of the day, but the attempt came too late.

A string of early French successes in the conflict ended in 1758, when the reforms and plans of

William Pitt began to make an impact. Thousands of British regulars were sent to North America, where they were joined by enthusiastic colonial militiamen. Major British strikes were made against

Louisbourg, the French bastion at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, and

Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio River. Those ventures succeeded, but a British drive against

Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga) failed.

Lieutenant Colonel James Bradstreet had served with distinction in the failed offensive at Fort Carillon. In the wake of that defeat he proposed an immediate strike against Fort Frontenac as a means to restore the initiative to the dispirited British soldiers. It was common knowledge that the fort was poorly defended, and consent was quickly given to the plan. Bradstreet assembled a force of more than 5,000 men, largely American militia and about 300 “battoemen” — colonists who built and manned small transport boats (

bateaux in French).

The army began its push northward in early August, halting briefly to begin construction of Fort Craven (later Fort Stanwix) at the present-day site of Rome, New York. This action was a means to seal off French forces on the Mohawk River and beyond. Having set that task in motion, Bradstreet marched on to Lake Ontario. Indians who were allied with the French noted the army’s movements and reported the news to Fort Frontenac; the commander there immediately sent a plea for help to Montreal. The British force moved by boat around the eastern end of the lake and occupied a position outside the fort on August 25. The besieging army surrounded its target and occupied a strategically important hilltop position nearby. The French garrison recognized the futility of its position and surrendered on August 27. All French ships, arms and ammunition were turned over to the British. Soldiers and civilians were allowed to depart for Montreal, where an equal number of British prisoners were to be released.

Bradstreet ordered the destruction of Fort Frontenac and quickly departed. The British were aware that the French relief force was on its way and held no interest in risking an engagement.

The fall of Fort Frontenac has been overrated by some historians. French contact with its more westerly installations was not suddenly cut off, as some have claimed. In fact, for a number of years most French supplies and reinforcements had traveled to the west by way of rivers, Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. The impact of this victory on British morale, however, should not be underestimated.

Later, following the War for Independence, American Loyalists formed a community on this site that came to be known as Kingston (Ontario). Fort Henry was erected there and served as a naval base for British and Canadian forces in the War of

1812.

See

French and Indian War Timeline.