Fort Duquesne

The point at which the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers join to form the Ohio River (La Belle Riviere to the French) has been known as the Forks of the Ohio, an area recognized for its strategic importance by early British and French agents.

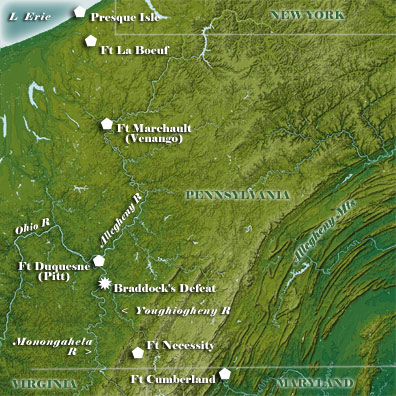

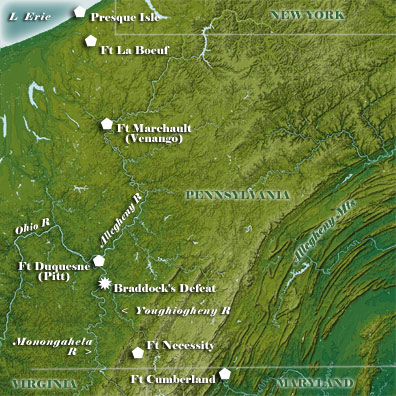

In the 1740s, William Trent, an English fur trader and entrepreneur, built a small trading post at the Forks. He conducted an active trade with neighboring Indian tribes and became wealthy in the process. The French noted the English presence and began to construct a string of forts in the area in the early 1750s; installations sprang up at Presque Isle, Marchault (Venango) and Le Boeuf.

Robert Dinwiddie, governor of Virginia and an active land speculator, responded by ordering the construction of a fort at the Forks to protect his budding business interests. In April 1754, Virginian construction forces began their labors, but were driven away by a vastly superior French force. Work was then completed on a structure that became known as Fort Duquesne, named in honor of the governor-general of New France.

The British made two efforts to regain control of the position, one by

George Washington later in 1754 and another larger venture under

Edward Braddock in 1755. Those events were among the earliest engagements in the French and Indian War, the final conflict in the

struggle between France and Britain for control in North America.

The British suffered a series of defeats in the war's opening years, but the tide turned in 1758. John Forbes gathered a force of 6,000 men at Fort Cumberland in western Maryland. This army included Washington’s contingent of 2,000

Virginia militiamen. Weakly defended Fort Duquesne was the target of this venture, but an early debate raged over the route to be taken to the Forks. Washington pressed hard for using the already existing Braddock Road, the path that had laboriously been cleared before the disaster of 1755. Others, including some with business interests in Pennsylvania, urged the construction of a new road through the central portions of that colony. Forbes eventually gave approval to the latter plan.

Progress on the new road was exceedingly slow; huge trees and almost impenetrable brush had to be cleared. Washington seethed over the wasted time, fearing that Fort Duquesne might be reinforced. Eventually the Alleghenies were crossed, which brought the British army close to its objective. An advance party was dispatched to gather information about the fort’s defenses. On September 14, Major James Grant unwisely enticed French forces into a confrontation and his British soldiers sustained heavy casualties.

An initial decision to delay the offensive until the next spring was forced by deteriorating weather conditions. However, Washington's soldiers managed to capture several enemy scouts and learn from them how poorly Fort Duquesne was manned. Few regular French soldiers were on hand and the Indian allies had deserted in large numbers. Washington ordered an immediate advance on the fort.

On November 24, the French commander recognized that he faced total disaster if he were to resist. Under the cover of night, the French withdrew from Fort Duquesne, set it afire and floated down the Ohio River to safety. The British claimed the smoldering remains on November 25 and were horrified to finds the heads of some of Grant’s Highlanders impaled on stakes with their kilts displayed below.

A contingent of British forces remained on the site and began to construct the new Fort Pitt, named in honor of the

secretary of state who had done so much to fashion a winning war strategy. Washington returned home where he would soon assume a seat in the

House of Burgesses and marry a young widow, Martha Custis.

The capture of Fort Duquesne coincided with the fall of

Fort Frontenac and the fortress at

Louisbourg. Considered together, they marked a great turning point in the war. The lesson was not lost on the Indian allies, many of whom deserted the French cause at this time.

Fort Pitt would be known as Fort Dunmore for a brief time in the early 1770s to honor the royal governor of New York and Virginia, but would revert to its earlier name during the War for Independence. The village that developed around the fort was called

Pittsburgh.

See

French and Indian War Timeline.